Down to Old Dixie and Back

by Jay Cocks

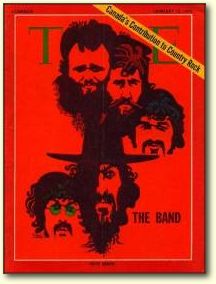

This article was the cover story in Time magazine, Jan 12, 1970.The text is copyrighted, please do not copy or redistribute.

it is not a commonplace river.

--Mark Twain,

Life on the Mississippi

In the Deep South, they have a saying that the closer you get to the Mississippi River, the better the music is. Down there, music lovers can easily tell whether a hot lick comes from 50 miles east of the river or 50 miles west; whether, in other words, it is East Texas blues, Delta blues or Georgia hill blues. If it gets much farther away than that, folks don't much care to know about it.

Cover of Canadian Time magazine, 01.12.1970 (The cover of the US magazine was slightly different.) |

Small wonder, then, that back in 1959 Jaime ("Robbie") Robertson, then a 16-year-old from Toronto, set off eagerly for points south, guitar in hand. "I was born to do it, man," Robertson recalls. "Born to pack my bag and be on my way down the Mississippi River. I was music-crazy, just a total music fanatic. I wanted to see all those places with those fantastic names. Chattanooga, Tenn.--wow! Shreveport, Lu-zee-ana --wow! I just couldn't wait to drive down that road, you know. All that good music came from there-- Robert Johnson, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Junior Parker--and they kept talking about those places in their music."

Over in Simcoe, Ont., a young butcher's helper and part-time bass-guitar named Rick danko felt a similar urge.

Driving up to his parents' home one evening in a friend's Cadillac, he cried out: "I've got to leave tonight; it's now or never!" He borrowed a coat, packed and was gone. One by one, Garth Hudson in London, Ont., Richard Manuel in Stratford, Ont., and Levon Helm, down on a bare subsistance farm in Marvell, Ark. (pop. 1,200), were making similar plans. To Helm, it was especially urgent. "You get out of school in May, and that's when you've already started planting cotton. You work from there right through till September, and the only break in there is the Fourth of July. I found out at about the age of twelve that the way to get off that stinking tractor, out of that 105-degree heat, was to get on that guitar."

Soon these five musical Huck Finns joined forces. As of the year 1970, they have played together for a decade. They have seen all the places that once sounded so magical. They have gathered up and stored a fair share of all that good nusic. Not only do they seem to know vhere all those hot licks come from, but they know where they should go. For years, practicing together for as much as seven, eight, ten hours a day, they played one- night stands in grubby towns all over the South and Canada. Later, they played invisibly behind Bob Dylan at the peak of his fame, learning from him and teaching him something in return. Now, as The Band--an intentionally unpretentious title-- they have come into their own. In the shifting, echoing cacophony of sound and sometimes fury that is the modern rock scene, The Band has now emerged as the one group whose sheer fascination and musical skill may match the exellence--though not the international impact--of the Beatles.

Trip or Treat

Significantly, The Band's music is quiet. They once played hard-driving, ear numbing rock. Now they deal in intricate, syncopated modal sound that, unlike most rock but like fine jazz, demands close attention and rewards it is vith a special exhilarating delight. When the Band plays it is not for a trip but a musical treat.Though their newest LP, The Band, is high on Billboard's "Top LP" chart and they have sold close to a million records, this does not mean that The Band will be everybody's cup of tea. But for those who take to them--musicians, college kids who have grown tired of the predictable blast-furnace intensity of acid rock, and an ever growing segment of the young--The Band stirs amazement and glee. Perhaps their most important accolade is the approval of scores of fellow musicians, who say simply: "The Band is where it's at."

The Band's sound is at first deceptively simple. It comes on mainly as country music full of straight lines and pure sentiments--in short, what Rock Critic Richard Goldstein has characterized as "pop nostalgia." But as you listen, new depths and distant sources emerge--and finally convince and captivate: Bach toccatas, folk tunes, commercial rock "n' roll, Scottish reels, the sound of Ontario Anglican church worshipers raising their voices in hymns on Sunday morning. The lyrics are spiritual and timeless. In Robertson's The Weight, written for the group's first Capitol album, Music from Big Pink (1968) and heard in the movie Easy Rider, cascading lines of melody combine with mock-serious lyrics to bring an Old Testament character face to face with a 1970 rock musician:

I pulled into Nazareth,

Was feelin' "bout half-past dead,

I just need some place where I can lay my head.

"Hey, Mister, can ya tell me where a man might find a bed?"

He just grinned an' shook my hand,

And "no" was all he said.

Words and music are delivered with unfashionable understatement. At four recent concerts in Manhattan's 4,500-seat Felt Forum (sellouts all), The Band showed a no-nonsense absorption in music that would have done credit to the Budapest String Quartet. Robbie Robertson's main contribution is as a composer of most of the group's songs and lyrics. But onstage he is a sedate figure who vaguely suggests pictures of James Joyce as a young man. With the bare trace of a smile visible under his mustache, his eyes often closed in what seems to be creative ecstasy, he stands punching out notes and laying out funky phrases like "the mathematical guitar genius" Bob Dylan used to say he was. Levon Helm approaches his drums with what is, in rock music, unparalleled subtlety and restraint. On bass, Rick Danko occasionally puffs his cheeks as if he were playing a horn. At the piano, Richard Manuel looks like a teen-ager masquerading as a pirate.

Behind them all, Garth Hudson rolls his bewhiskered, bearlike head from side to side and pedals his organ with stockinged feet. Garth is beyond question the most brilliant organist in the rock world. His improvised variations, drawn from a vast knowledge of popular and classical music, provide both decorative scrollwork and depth to The Band's total impact. He also sprinkles each number with unexpected and attractive sounds that always seem to come as a predictable surprise, like the emergence of a cuckoo from a cuckoo clock. The drone of a jew's-harp, which serves as a musical bridge in Up on Cripple Creek, is actually produced by the wah-wah pedal on Garth's clavinette. But whatever they do, The Band tends to treat the audience as they would themselves. That means no cutsie-pie patter, no use of microphones as phallic symbols a la Mick Jagger--and no pelvis-pushing onstage or in the aisles.

Can this be rock? The straight, the uninformed or the middle-aged may ask. What happened to all those groups whose names sounded like Self-Adoration, Pathetic Fallacy, or the Small Bores? The answer is: nothing. They're all still there blasting away at a decibel rate that is really delectable only if the listener is high, so that his senses are transforming sound into a mind-blowing experience. Hard rock, acid rock may never die--for one thing because their main constituents, groupies and would-be groupies, are now and always will be less interested in music than in the male personalities of the performers.

Yet rock music today, some 15 years after it first laid siege to the heart and middle ear of youthful America, is a various and many- splintered thing. This is partly the result of wealth (which allows experimentation). Partly it is the re- sult of refinement. There are tens of thousands of rock groups. The most musically gifted players are developing and growing up.

Blending Styles

Musical mergers have bred mixtures that all but defy Mendel's law. Groups like Peter, Paul and Mary, and Simon & Garfunkel practice folk rock. Joe Cocker and Janis Joplin lean toward soul rock. Blood, Sweat & Tears and Chicago are into jazz rock, and that is just a beginning. In such groups, the influence of classical has brought about blends of jazz and rock rhythms with composers as diverse as Satie and Bach. Even the classical violin, or rather its electrified sister, has made the scene in the playing of a hard new blues band called the Flock.Beyond style, rock is blending with other forms--in rock-backed ballet, and in attempts at creating rock opera. Despite a pretentious libretto and hardly any structure (it is really a song cycle), The Who's Tommy has profoundly stirred millions of listeners with a story about parental hatred and the resulting rise and fall of a pop-generation dictator. Lately, considerable air time in the U.S. and England has been devoted to Superstar, a soaring, foot-tapping single from a rock opera about Jesus Christ, now being written in London. Sample lyrics:

Did you mean to die like that? Was that a mistake or

Did you know your messy death would be a record-breaker?

... Jesus Christ Jesus Christ Who are you? What have you sacrificed?

Jesus Christ Superstar Do you think you're what they say you are?

Perhaps the broadest shift in rock fashion is the one exemplified by Creedence Clearwater Revival, Crosby, Stills. Nash and Young, and most of all by The Band. Though The Band calls it "just music--everything we've ever heard or done," the convenient label is country rock. However labeled, it is a turning back toward easy-rhythmed blues, folk songs, and the twangy, lonely lamentations known as country music. Country rock is also a symptom of a general cultural reaction to the most unsettling decade the U.S. has yet endured. The yen to escape the corrupt present by returning to the virtuous past--real or imagined--has haunted Americans, never more so than today. A nostalgic country twang resounds all up and down the pop charts. Glen Campbell and Johnny Cash, two singers once chained to the old country circuit, are now national figures with coast-to-coast network shows. Commercialized even further, the country strain runs into advertising--most egregiously in Salem cigarettes' unwittingly ironic paean to the joys of fresh air.

Irony-Proof Vision

The thoughtful young have led the way in declaring disenchantment with the present. But for the perceptive and rebellious, no slickly packaged nostalgia will provide escape or inspiration. Nor are they to be taken into the near-camp of Grand Ole Opry. In yearning for an irony-proof vision of a better, gentler life and more enduring values, the young have been turning for years toward solace as various as Zen and hi-pie communes. In pop music they are now turning toward The Band. In part, this is because The Band's words and music suggest that The Band itself has been there and back. "It's hard to describe," says an Amherst senior. "They're sophisticated, but the very words and music that make them so appealing move away from sophistication to earthy, honest qualities in life." Another adds: "You listen and you just know that's no group of johnny-come-latelys from the suburbs who've gone off to a commune while Daddy foots the bill."Among other things, The Band's unidealized look into yesterday includes a rare subject for pop music: consideration of the old. "Most people are knocked out by younger people," Robbie Robertson explains. "I'm knocked out by older people. Just look at their eyes. Hear them talk. They're not joking. They've seen things you'll never see." Rockin Chair, on the latest Band LP, sketches in the weariness of old age better than pop music has any right to do:

Hear the sound, Willy Boy,

The Flyin' Dutchman's on the reef, It's my belief,

we've used up all our time,

This hill's too steep to climb,

And the days that remain ain't worth a dime...

Even the group's most lingering look back at life on the land, King Harvest, is touched with a double vision. is marked by an ironic interplay between the rich, yet somehow threatening sound of nature and the querulous, grass- opperish whine of the farmer.

"I'm glad to pay those union dues," the farmer sings. "Just don't judge me by my shoes." But then comes the refrain. With Danko and Robertson on guitars, creating a controlled hush that is just the right rustling background, ManuelI and Helm sing in low unison:

Corn in the fields,

Listen to the rice when the wind blows "cross the water.

King Harvest has surely come.

Music fans who turned up at record stores to buy The Band's first album, Music From Big Pink, were confronted by a rather odd but decidedly cheerful slip case. On one side were some pastel-colored creatures purporting to be The Band. Though it seemed clear that they had been created by somebody's gifted kindergarten son, the credit line truthfully assigned the artistry to Bob Dylan. On the inside cover, a phalanx of figures appeared--some 35 in all--who turned out to be The Band, backed by most of the members of their respective families. It is characteristic of our age that many people thought the family bit had to be a put-on. It was not. "We don't see our people all that much," Robertson says. "But we get sick and tired of all these whiny rock groups who are always bitching about their parents."

In Dylan and their parents, the group had paid respects to two of the major forces in their musical lives. All five took to music young, and they were brought up singing and playing hymns and folk songs with their families. The only American, Levon, was playing mandolin, drums and guitar in his early teens, and once won first prize at a county fair, accompanied by his sister on a homemade washtub bass. Rick Danko, whose father is a Simcoe tobacco farmer, was given a mandolin at five and soon joined his three brothers at Saturday night musicales.

Garth, the son of a World War I pilot turned agricultural inspector, went farthest in formal study, getting through his first year in music at the University of Western Ontario before taking to the road. Before that he had helped his father rebuild two pump organs and worked through much of Bach's keyboard music (The Well-Tempered Ciavier, some 300 chorales). He also briefly played sepulchral organ in his uncle's funeral parlor. "It was terrible," he recalls. "A terrible business."

Robbie was the only big-city boy. He lived with his widowed mother in Toronto and played serious guitar at twelve. Richard was the only reluctant musician in the group. His father, a Chrysler mechanic in Stratford, saw to it that he had piano lessons. But he hated practicing--until he learned he could attract girls by playing in a band.

The Rabelaisian Life

One result of all that music is that four of the five members of The Band can and do sing professionally, and the group actively plays 15 different instruments among them. In the cashless, lean and hungry days, that kind of versatility helped keep them employable. In particular, it made them attractive to Ronnie Hawkins, the stormy but curiously attractive personage who first beat them into shape as a playing unit.Hawkins billed himself as "the king of rockabilly" (an ancestor of country rock--by rock'n roll out of hillbilly). Calling the members of his band The Hawks, he led them from the grubby nightspots on Toronto's Yonge Street to clip joints in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi. "Those places were so tough," Hawkins now likes to recall, "you had to show your razor and puke twice before they'd let you in."

A fine front man, Hawkins had a Rabelaisian capacity for talk, among other things. Yet by The Band's accounts, his memories are little exaggerated. "At one bar in Dallas called the Skyliner Club," says Robbie, "they had these dancer chicks, and one of them who was dancing had only one arm. It was a rough joint. Bullet holes in all the walls."

On the money side, things were grim. The group occasionally had to work together in grocery stores, one buying something like a loaf of bread while the others tried to steal what they could. "We didn't have nothing to eat," Robbie explains. "And no money." One night, really desperate, Levon and Robbie decided to stick up a crap game with a pot that often ran to $7,000 or $8,000. With masks made of pillow cases they moved out on their mission--only to find the game had broken up early and everybody was gone.

"Hawkins," a friend says, "worked the living hell out of those boys." But the years with the king of rockabilly were not wasted. "He could be funny onstage," says Danko, "and he taught us a lot about music and life." Well, life, anyway. Hawkins liked to throw all-night parties in his apartment above Toronto's Le Coq d'Or club. "Ahh, boy," recalls Manuel, "lots of 'bring out the wine and turn the music up', lots of people in one room just sweating." That one room usually drew a large slice of the unsalubrious downtown playboy set. "The more parties you had," says Manuel, "the more people would come to the nightclub, "cause they were hoping to get invited to a party later." With Hawkins cheering them on as a Mephisto-like master of ceremonies, they reveled in a horror chamber of life: the whole scene, with pot and pills thrown in as a matter of course. Somehow they emerged on the other side unscathed.

Also they began to realize that they had nothing more to learn from Hawkins. A musician they could learn from was Bob Dylan, and when in 1965 he suddenly asked them to join him for a tour, they quickly accepted. "We knew who he was," says Robbie, "but we didn't know he was near as famous as he was." That was the point in Dylan's life when he turned his back on his folk-purist fans and met rock head on. The rock he met was provided by The Hawks--who became known as "the band." The result was folk rock. In some ways, that was the most decisive moment in rock history. One reason is that rock thereafter began to make increasing use of the modal harmonies then prevalent in folk music. "Yeah, Dylan's the one who really mixed everybody up, which was definitely a good thing," says Robbie. "It opened a lot of doors and closed a lot of doors."

They did not always understand the surrealistic lyrics Dylan then favored. Says Robbie: "We were used to singers who opened their mouths and went "Whop bop bop lu bop,' but Bob decided to say something while his mouth was moving, and it was interesting to see how easy it came to him." What also impressed the group was the kind of music they were now making, though it was still loud and eruptive, like the life they led. "It was like a volcano going off." Most people agreed, including Actor Marlon Brando, who once told them: "The two loudest things I've ever heard are a freight train going by and Bob Dylan and The Band."

Just Living

The Band plays differently today. It lives differently too. Both changes reflect a period of contemplation, and a hard-earned equilibrium. Three of them --Robertson, Manuel and Danko--have lately married and have small children born within months of one another. In 1966 the group drifted up to Woodstock, N.Y., to be with Dylan after he broke his neck in a motorcycle accident. As he recuperated, they all played music together informally. Three songs on the Big Pink album also resulted, most notably Dylan's own I Shall Be Released. Dylan has since left his house there and moved to Greenwich Village. But The Band plays on in Woodstock. "We didn't just knock off," Robbie tells it. "We were doing some things up there. But we weren't out there in front any more. We were fooling with film and stuff and making tapes and hanging out and doing this--what we do up here --well, just living."After so long on the road, growing up to quiet was not easy. "Getting healthy," Danko jokes, "is getting up in the morning instead of going to bed in the morning." Another member of The Band describes the transformation thus: "Well, we were shooting films up here, and then we were shooting vodka, and first thing you know we took to shooting fresh air. What a habit."

Keep It Flat

The Band's main effort today in music and life is to try to keep things simple and natural. Personally, this mean as much freedom and informality as possible within a framework of intense professional discipline. The group could use a leader and front man but does riot have one because, as they explain "nobody wants the job." Musically, the new style means little or no showmanship and as little jiggering around with electronics as possible. "When people make records now," points out Robbie "they make things very bright. If you want to hear everything, turn up the treble. We decided not to do that. Whatever sound we were going to get, we would get it in the room, not by using some machine. Just record it flat, and not use echo. On our second album we did use the bathroom as an echo or the chorus of Jawbone, but that's all."Though they once played for $2 each a night, they now turn down $20,000 if the scene seems wrong. When they went to California to make their second LP, they wanted things just like their informal sessions in Woodstock. After a struggle, they avoided a sound studio with wrangling engineers, on-again, off-again schedules. Instead, Capitol fitted up a pool house that used to belong to Sammy Davis Jr. The group tinkered with the knobs themselves and worked at do-it-yourself recording pretty much when and as they pleased. Recently, they walked out of a guest apearance with Glen Campbell because they could not do it live--Campbell wanted them to sit on barrels in a pickup truck and silently mouth songs to their own recorded music. Given so much longing for simplicity, they are choosy about movie offers. The newest script we got," Robbie snorts, "was called Jesus Christs." Robbie is compiling songs for a new album. Until they make it--probably in the spring--they will do more concerts, calling their shots and places at suitable intervals, rather than launching the kind of all-out tour seen in the Rolling Stones recent invasion of the U.S.

Somewhat distrustfully, the members of The Band have acquired a few of the trappings of big success. Their new Woodstock houses, perched on hills outside the village. A new recording studio. Levon's zippy gold Corvette. Garth's stately black Mercedes. Before tasting that success themselves, they faced--vicariously through Bob Dylan--the kind of assault on time, privacy and sponaneity that fame and personal success can make on pop musicians.

They have come a long way from home to get where they are, on a harder road, requiring a greater need for growth, endurance and devotion to music than most flash rock groups ever have to display. They seem well prepared to stay as they are. In a commercialized, McLuhanized, televised, homogenized world, care and craftsmanship have to be cultivated as a matter of personal faith. Experience telescope and the young learn fast when they learn at all, sometimes in a few years of running through a range of experience and self-realization that once use to take decades. What The Band has worked out is something that countless other Americans hope for, a sort of watchful, self-protective truce within an encroaching world of noisy commerce. Robbie Robertson said it for them a when he was asked if they worry about being uninvolved, about living such a isolated life. "Live outside what's goin on?" he replied. "Well, look what's going on. You almost have to live outside or you lose it. You lose everything. You become your own joke."

The Band Talks Music

ROBERTSON: Your roots really are everything that has ever impressed you and how much of it you can remember. A bridge from a song by Little Milton seven years ago might start you off on something; that's how loose it is. Maybe you'll never even remember it. There are five guys involved, and everybody has a little different thing. Like one guy in the group would remember very impressive horn lines by Cannonball Adderley. Somebody else would remember a singing harmony that J. E. Mainer and his Mountaineers did yeaes ago. Over all the years we've been playing, we've been buying thousands of records by people nobody remembers the names of. Just the music. Right up to Edith Piaf.HUDSON: I found out I could improvise; I probably found out too young. I could never really adhere very strictly to classical music, could never become a good classical player. Could never get anything "down." It amazes me what the classical people have to go through to get something down so that it happens every time. It's really superhuman to maintain the kind of quality that's required.

The "churchy" feeling in their music:

HUDSON: I never think of any hymn at any time. It's an idiom. You're acquainted with the movement and the way that it sounds. The Anglican Church has the best musical traditions of any church I know of. It's the old voice leading that gives it the countermelodies, and adds all those classical devices which are not right out there, but they add a little texture. If you look at Bach's three or four hundred chorales, you'll find every rule and every kind of chord that's ever been used since, but it's snuck in so discreetly you don't pick it up as being definite dissonance. You don't realize that he's playing a minor ninth--what we call a minor ninth in dance-band terminology--because it will lead to another chord which will be harmonious or simpler in harmonic texture.

The basic ingredients of rock'n roll:

ROBERTSON: People say rock'n' roll is a combination of rhythm and blues and country-and-western, but really it's just blues and country. White music has always been very ricky-ticky, steppity-step, plunkety-plunk-banjo. You could always imagine a stiff collar behind it. Country music was played by white people, and blues was played by black people. And when it interchanged, it became something else, which is what Levon's father sings like. He sings blues with a twang, with that different accent, with a different bump on a different place. The new Rolling Stones album sounds like bunch of blues-oriented cowboys, man, no doubt about it. Some people call what they do classical rock, or jazz rock, or folk rock. But what we play is really just rock'n roll. It's the same music we've been hearing for the last decade and a half. People like Little Richard or Elvis or Fats Domino--these are the people we're carrying out the tradition for, or trying to. I watched a little bit of the Tom Jones Show, and that's when you really learn to appreciate Elvis.

Songwriting:

MANUEL: I lean more into chord changes and melodic stuff. I can write music very easily, but when it comes to words, I cringe. It's hard to get those words in the right slot, to just get going.

ROBERTSON: Sometimes it's just "whoopie" you've got a song. That's the best way, when it just comes upon you and you've got to stop doing everything. It's wondrous. It's what makes you want to write songs. The other way you've got to tug and struggle. It works, but it isn't so rewarding. When you're done, you're just relieved to be done. When I learned the ABCs, I learned that when you write something, you should write something that's not only going to be appreciated today but tomorrow too, or yesterday. The best you can do.

Themselves and staying together:

DANKO: We have five people to bounce things off of. Everybody has their spiritual side, which is nice. One week the spiritual end might come up a little heavier on Garth than on Robbie. You know, the holding-it-together.

ROBERTSON: When I started playing the whole age of acknowledgment hadn't come yet, when people were saying "Wow." I never said "Wow." I just did what came, you just ate what was put in front of you. People treat us so much more intellectually and so much heavier than what we ever believe for a minute that we are, and we feel kind of foolish. I wish it was magic upon magic, but its no big thing. There's no point in writing about it, talking about. Let's just listen to it.

Music in general today:

ROBERTSON: People have to look at a tin can as art and say "Wow." I can't believe that people are so gullible to accept what they accept in art and in music. Nowadays they're playing jock-traps and feedback, and they knock them out. I guess there's enough people to go around and anybody can get lucky. I think it's up to the individual to get himself to the place where he doesn't have to be that taken in by anyhing. Now people are saying, let's hear he truth; we haven't heard it in a long, long time.